Creator's Statement

Statement by Sikata Banerjee

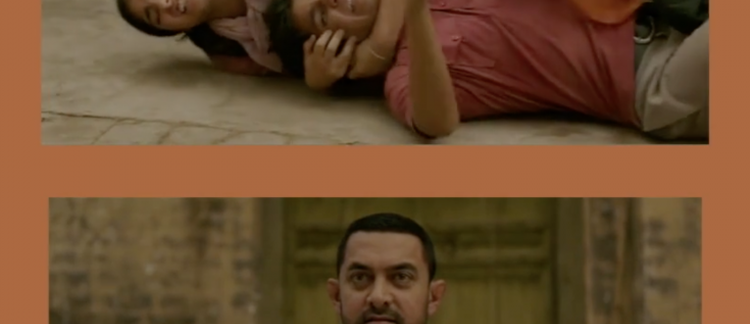

This video essay analyzes two popular and critically acclaimed films, Chak de! India (2007) and Dangal (2016), hailed as “feminist,” through the theoretical lens of a gendered vision of nation, which I term muscular nationalism. Although both movies are projected as journeys of female empowerment, two men, Kabir Khan and Mahavir Singh Phogat, are the true protagonists. In the former, the Indian field hockey team coached by Khan, and in the latter, wrestlers, Geeta and Babita trained by Phogat, win international glory for India through their grit and strength. The men are the real winners and the films celebrate their success and redemption.

This study is informed by McClintock’s (1993) argument that popular film is an important vehicle for the circulation and recreation of dominant visions of nation. Further, scholarship (Nandy 2006 & Virdi 2003) has eloquently argued that Hindi language popular film (or Bollywood as it is sometimes known) in India is a wide-reaching medium for the dissemination of dominant nationalism. At this cultural juncture, a particular nationalist triumphalism, coinciding with globalization and often unabashedly Hindu, has shaped the circulation and consumption of a muscular view of India (Banerjee 2016). Nationalism is a gendered affair in popular film. This submission is a comparative exposition of how the films’ narratives accommodate athletic female bodies within muscular nationalism.

For the past several years my analytical inquiry has been guided by a theoretical concept, muscular nationalism, which focuses on the intersection of masculinity and nation. Muscular nationalism is animated by an idea of manhood associated with martial prowess, muscular strength, and toughness. My research on the fusion of masculinity, nationalism, and Hinduism informed by extensive field work in India led to the development of this concept. My book (Banerjee 2012) presented a multi-faceted analysis of muscular nationalism while a more recent work (Banerjee 2016) examined the dissemination of this concept through popular film. After the completion of this project, I began my collaboration with Niall and Rachel who had experience in creating video essays and it seemed to me this was a compelling medium in which to explore the location of women’s bodies in this view of nation.

These women’s sports movies are consistent with muscular nationalism. An important normative and physical signifier of this interpretation of manhood is victorious athleticism (Anderson 2005 & Burstyn 1999). For example, in the United States, the Super Bowl opening ceremony is a celebration of masculinity, nationalism, and martial prowess. India’s present nationalist triumphalism is frequently expressed by male bodies and masculinity.

The central problem this essay addresses is the position of women and femininity in muscular nationalism. Research (Banerjee 2012 & Enloe 1990) has shown that, normally in this vision of nation, women are passive, chaste objects expressing national moral honor, protected by masculine warriors. However, this study focuses on the manner in which popular culture envisions women who take on the active task of projecting national strength and glory. These female bodies don’t necessarily masculinize themselves but certainly deemphasize markers of femininity: sexual desire and long hair. Further, as the two films reveal, this feminization of national strength must be nurtured by masculine guidance and draws meaning from the redemption of masculine failure.

In Chak De! India, a Muslim man, accused of betraying the Indian national team, must show his allegiance to (Hindu) India by erasing any marker of his faith and representing a hyper-patriotism through coaching the Indian women’s field hockey team. Given the rise of Hindu nationalism, the depiction of Kabir Khan (portrayed by Shah Rukh Khan, a Muslim actor) as coach is especially poignant as is another great Muslim actor, Aamir Khan, playing the father-cum-coach in Dangal. Bollywood films have struggled to accommodate the Muslim body in their narratives. A common story telling device is the “good” Muslim –“bad” Muslim binary. Kabir Khan is a “good” Muslim. Handsome, well-spoken, he bears no markers on his body proclaiming his religion, nor is he depicted praying in a mosque or participating in namaaz. He is happy to declare his steadfast patriotism by saluting the Indian flag and coaching the team to redeem his honor by bringing glory to his nation. He opposes the “bad” Muslim portrayed by menacing terrorists who wield their religion as a weapon (Rai 2003). Yet Chak De! maintains a sexual firewall between Kabir (Shahrukh) Khan’s Muslim body and the senior players, Vidya and Bindia, despite their attraction to him. The focus stays on his proving his patriotism by disciplining his players.

In conclusion, this videographic essay argues that female bodies are suspect if they independently reach towards an expression of muscular, national strength and thus need to be guided, perhaps policed, by masculine energy. Put another way, this centering of the masculine, in a story of women’s empowerment, can be seen as a social strategy of accommodating women and femininity in a story of a nation that is unapologetically masculinized.

Works Cited

Anderson, Eric. 2005. In the Game: Gay Athletes and the Cult of Masculinity. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Banerjee, Sikata. 2016. Gender, Nation, and Popular Film in India: Globalizing Muscular Nationalism. Routledge: London.

Banerjee, Sikata. 2012. Muscular Nationalism: Gender, Nation, and Empire in India and Ireland. New York: NYU Press.

Burstyn, Varda. 1999. The Rites of Man: Manhood, Politics, and the Culture of Sport. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Enloe, Cynthia. 1990. Bananas, Beaches, Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

McClintock, Anne. 1993. “Family feuds: Gender, Nationalism and the Family.” Feminist Review 44: 61-80.

Nandy, Ashis. 2006. “Introduction: Popular Cinema and the Culture of Indian Politics.” In Fingerprinting Popular Culture: The Mythic and the Iconic in Indian Cinema, edited by Vinal Lal and Ashis Nandy, i-xxvii. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Rai, Amit. 2003. “Patriotism and the Muslim Citizen in Hindi Films.” Harvard Asia Quarterly. Summer: 4-15.

Virdi, Jyotika. 2003. The Cinematic Imagination. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Biographies

Sikata Banerjee is Professor of Gender Studies at the University of Victoria, Canada. Her work focuses on gender and nationalism in India. She is the author of Warriors in Politics: Hinduism, Nationalism, Violence, and the Shiv Sena in India (Westview 2000); Make Me a Man! Masculinity, Hinduism, and Nationalism in India (SUNY 2005); Muscular Nationalism: Gender, Violence, and Empire in Ireland (NYU 2012); and Globalizing Muscular Nationalism: Gender, Nation and Popular Film in India (Routledge 2016).

Rachel Malia Newkirk graduated with degrees in Sociology and Film Studies from Fairhaven College, Western Washington University (WWU). Her video essays and films can be found on Vimeo and YouTube. Rachel works as a Social Media and Marketing Specialist and Editor for film festivals around the country.

Niall Ó Murchú is professor of global studies and political economy at Fairhaven College, Western Washington University (WWU). He has published articles in political science, sociology, and applied philosophy in Comparative Politics, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Irish Political Studies, International Journal of the Sociology of the Family, and The Journal of Human Development and Capabilities. His video essay “A Place in the Nation” was published in [In]Transition (5.2). His current research projects focus on film and nationalism in Ireland, Korea and Palestine.

Reviews

Review by Anupama Kapse

The global resurgence of extreme nationalism has become one of the most pressing cultural questions of our time. How the sport film feeds nationalism’s intransigence is the topic of Banerjee’s, Newkirk’s, and Ó Murchú’s video essay. Focusing on the martial, hypermasculine qualities of Hindu nationalism in India, Banerjee et al turn to the massively popular and now-iconic Chak De (2007) and Dangal (2016). In keeping with the expository thrust of their video, the work is structured by clips that demonstrate a governing tension between male strength and female docility.

One of the most striking aspects of this study is the revelation of exhausted, enervated and fatigued male bodies as they join an army of symbolically martialized nationalists. To offset this irony, Banerjee et al choose clips that reveal a fit, athletic and indefatigably energetic female body politic. While both Chak De and Dangal are indeed sport films, their focus on women in field hockey and dirt wrestling roots global sport genres in the Indian soil, setting them apart from the many indigenous, mostly all-male cricket films that popularized the genre in Bollywood, starting with Lagaan (2001, also starring Aamir Khan). Proliferating female bodies break new ground as they reaffirm nationalist solidarity against an expansive global backdrop. Equally, women stand out in sharp relief as “key players” and “game changers” in the history of the sport film as a sensational, ongoing cultural repository of nationalist theatrics.

If the excessive demands of muscular nationalism seem to burn older men out, young women—as the bearers of new physical energies—are called upon to compensate for aging, beleaguered and often marginalized male counterparts, at the expense of their own feminine desires and sexual fulfillment. Visually, muscular nationalism, the essay’s core conceptual framework is most effectively demonstrated in the clip where coach Kabir Khan “tames” a roomful of robust female hockey players into compliant silence.

Despite the intensity of such sequences, several clips show how women counteract the commanding presence of an authoritative male coach. Friction between male authority and female defiance is pleasurably mined by the both films as disobedient female bodies perform comic routines and tongue-in-cheek lyrics so specific to the Hindi sport film’s playful style and oeuvre. Take, for example the edgy, rough, husky timber of the song “bapu, tu to sehat ke liye hanikarak hai”/“oh father, you are harmful to my well-being,” gleefully upending a scene of forcible hair-cutting. A plethora of unruly women in intense bodily combat allows viewers to glimpse the forbidden and hear the tongue-in-cheek as they contest the supremacy of a majoritarian muscular by turning it on its head.

Take, too, the segment where a young Hindu woman hits upon a disfavored Muslim coach who rejects her sexual advances, which remain tellingly off-screen. The clip affirms Khan’s moral authority, while a sentimental male voice mourns the Muslim man’s marginal status as the third color of the Indian flag in the song “teeja tera rang tha main toh”/“I was your third color.”

Despite the presence of these pleasurable and/or tearful eruptions, in both films sporty attire and the kinesthetic movements of attractive female bodies pour old reformist wine into newly muscular nationalist bottles. Drawing attention to young women as torchbearers of a freshly sexualized vigor, with men watching as benevolent, if highly disciplinary father figures, Banerjee shows how, if the muscular can take hold, it can do so only by appealing to feminist guarantees that take the form of female compliance. This may well be how the sport film genre reimagines collective group identity so effectively—by presiding over individual gender and religious affiliations—to the extent that the genre can repress the Muslim identity of powerful male stars like Shah Rukh Khan and Aamir Khan, while women become their foot soldiers.

Review by Sujata Moorti

If Benedict Anderson presented the nation as an imagined community facilitated through print capitalism, Indian cinema offers a useful counterpoint to provincialize this idea. In Indian cinema, particularly Hindi cinema, the nation is repeatedly articulated as a deeply gendered concept. This essay limns how 21st century concerns are refracted through the prism of gender in contemporary Hindi cinema. Earlier films showcasing female protagonists eschewed the term feminism. Strikingly both movies under consideration embrace the term feminism but the gendered politics they promote are at some remove from a feminist politics. The essay reveals beautifully how the term feminism serves as an alibi to recenter the male hero. The athletic prowess of the women serves as a counterpoint to the flaccid masculinity of the heroes. The essay reveals how the films’ representational politics help recalibrate gendered notions of the body, particularly those of the male protagonists. The hair scenes depicted in the essay underscore how the female athlete’s success is underwritten by neutering her. This insight that female sexuality can be disarticulated from the nation helps underscore why neoliberal cinematic representations of the nation are dramatically different from previous iterations of the gendered body of India.