Creator's Statement

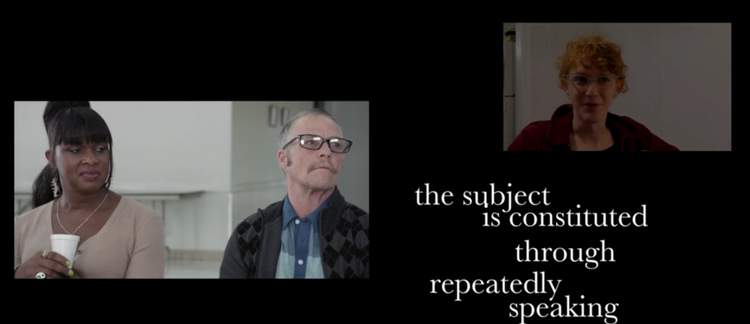

West Side Story, on both stage and screen, remains one of the most significant and influential creations in musical genre history thanks to its precise integration of story, music, performance, and dance. Choreography’s narrative centrality in the 1961 film adaptation (directed by Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise) is the focus of my video essay, “America is (not) Cool.” The film’s formal use of dance merits greater attention, and my essay demonstrates this through a multiscreen analysis of two key dance sequences: “America” and “Cool.”

By juxtaposing “America” and “Cool” in their entirety, my work emphasizes the choreographic [1] and cinematographic parallels that strengthen the narrative ties between the two. The choice to analyze movement in motion shifts us from an intellectual study of the choreography within its cinematic context to an intuitive one, to use Henri Bergson’s categorical separation of scientific and perceptual knowledge [2]. By avoiding immobility in my videographic analysis, I hope to provide the viewer with analytical and observational findings that cannot exist in written scholarship. As a result, minimizing my editorial changes to the numbers’ temporality was a priority. To accomplish this, I imposed several strict editing parameters in creating this work:

Playback of the two sequences is synchronized to the start of each musical number, beginning with the earliest suggestion of musical number content. For “America” this begins with the sounds of nondiegetic percussion music, for “Cool” this begins with Ice’s interjection of “they’ll laugh!” which, with the illumination of the car headlights, silences the group. The initial appearance and final disappearance of each number on the image track indicates the beginning and end of the musical numbers.

Both numbers play in their entirety with no modifications to the timing or order of shots or soundtracks, even if at times both “screens” display the visual content from one number or the sound from one number is absent.

As the opening epigraph to my video essay indicates, finding a medium-specific aesthetic was a central concern to Robbins in adapting his work to the screen. To allow the viewer to observe the numbers’ editing patterns, and the resonances between them, all edits within the playback of the numbers are original to the film. When “Cool” takes the place of “America” or vice versa, it is the result of either a shot ending in one number or a new shot beginning in the other.

To draw attention to my analytical findings that result from this juxtaposition, my edits therefore focus on sound mixing, when and where to display the visuals of each number, and the position of the screens relative to one another.

The complex rhythmic resonances of each number’s choreography become apparent when the dancing from one plays with the music and lyrics of the other. However, this juxtaposition demonstrates that the Sharks—Anita and her fellow female Sharks, especially—can more effectively “adapt” to the rhythms of both, whereas the Jets struggle more to integrate with the Sharks’. Moreover, Ice’s lyrics in the beginning—“easy does it,” “stay loose,” “play it cool”—emphasize that the Jets need to adopt qualities of lightness and free flow if they are to avoid raising suspicion after the events of the rumble, qualities that the Sharks already possess and demonstrate in their choreography as Ice sings those phrases.

The choice to arrange the images horizontally, rather than presenting them one on top of the other, emphasizes the attention Wise and Robbins gave to off-screen space in their staging of the choreography [3]. In both numbers, framings range from long shots to show the ensemble to close-ups of lead characters (Anita in “America” and Ice in “Cool,” especially). Even in more distant framings, the choreography often exceeds the space of the frame to create expansive lines of lateral movement that extend off-screen. When the numbers are placed side by side, this creates a hybrid space in which the Jets and Sharks dance both with and against each other. For example, at 2:43 Anita moves frame right away from Bernardo in the left screen, towards the Jets, only to appear soon after in the right screen moving frame left, having circled around the Jets in the multiscreen space.

Closer framings of characters use the eyeline matches of the original numbers to suggest additional interactions between the two groups. Some are more playful—Ice’s lyrics in his close-up at 2:07 could function as mischievous advice to Bernardo given his flirtatious conflict with Anita at that moment—while others parallel the violence of the narrative, as when A-Rab “shoots” the Sharks at 2:56. The horizontal multiscreen layout creates a unified space, shared at times harmoniously and at times reluctantly, to draw attention to the parallels of staging, editing, and choreography.

In juxtaposing these two numbers, my work creates a hybridized musical number from the contents of “America” and “Cool” that changes the meaning of the original sequences to ultimately intensify the narrative, rhythmic, spatial, and at times sublime, parallels between the Jets’ and the Sharks’ performances. The result emphasizes the tragic tone of West Side Story’s narrative in our observation that there is more unifying these teenagers than there is diving them. The direct interaction of the two numbers suggests what the groups’ relationship could have been—teasing yet harmonious, given their numerous similarities—as opposed to what it is—confrontational and violent, given their mutual bias towards one another and their incompatible differences. The juxtapositions created in my editing choices demonstrate the aesthetic depth of Robbin’s choreography and dance’s crucial role in the film’s narrative.

Notes:

1. My analysis is supported by the methodological rigor of Laban Movement Analysis, a system that provides a comprehensive vocabulary to describe the expressivity of human movement.

2. Bergson, Henri. The Creative Mind: An Introduction to Metaphysics. Trans. Mabelle L. Andison. Mineola: Dover, 2007.

3. Robbins left the film production of West Side Story before all musical numbers were filmed, but shooting schedules confirm that he was still on set when both “America” and “Cool” were in production. Wise, Robert. Memo to Al Wood. July 27, 1960. Jerome Robbins Papers, New York Public Library.

Bio:

Jenny Oyallon-Koloski is an Assistant Professor in Media and Cinema Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a Certified Movement Analyst (CMA) through the Laban/Bartenieff Institute for Movement Studies. She studies movement on screen, the musical genre, and the films of Jacques Demy. Her work has appeared in Studies in French Cinema and PostScript.

Reviews

Review by Cara Hagan

Jenny Oyallon-Koloski’s video essay, "America is (Not) Cool," is a juxtaposition between two iconic dance numbers from the 1961 movie musical, West Side Story – a work that arguably set the bar for cinema adaptations of live musicals in the American canon and catapulted choreographer Jerome Robbins into the choreographic ether. In a simple split-screen format, viewers are invited to observe “America,” featuring the Puerto Rican teenagers in the story, and “Cool,” featuring the White teenagers in the story to great effect. The pieces, about the same duration, are cut together from start to finish and present both visual and sonic interplay that bring to the fore aesthetic and thematic through lines and ironies in the work.

Observing the two pieces side-by-side affords the viewer the opportunity to observe ways in which each piece may serve to punctuate the other at key moments – for example when the car lights turn on to illuminate the dark garage the White teenagers occupy at the beginning of their piece, we are transported to the relatively bright rooftop where the Puerto Rican teenagers will have their number, as if the car lights are the source of that brightness. Throughout the piece, more subtle punctuations and allusions help to create the possibility of a world that is not two separate spaces, but both spaces together that include space off screen that is indicated when limbs and people disappear from view while the action continues.

Rhythm plays an important role in this juxtaposition, highlighting places where the two pieces are harmonious, giving the viewer the chance to witness some of the choreographic motifs explored throughout the musical as a whole, while also being able to observe how the two groups are styled differently to fit the ethos of their context in the play. Places where rhythm and movement are in opposition give rise to insight into the tensions being explored in the work as a whole – teen angst, the awkwardness of social interactions (both casual and charged) and the need to find or create, safe, comfortable space together, whatever the cost.

One irony that cannot be overlooked in this presentation is the racism of Hollywood on display in a movie about such difference. While the plot of West Side Story was touted as one that explored cultural tensions and the effect intolerance can have individuals and communities, seeing the two numbers side by side heightens the experience of seeing multiple actors in brown face. Rita Moreno, the actual Puerto Rican actress who played Anita in the movie was forced to wear dark make-up, along with her white counterparts! In addition, one observes Jerome Robbins’ modern jazz dance and Leonard Bernstein’s music, clearly inspired by the cool jazz movement of the 1950s, at a time when the influences of African American artists on mainstream American entertainment and the fine arts was being downplayed or erased altogether.

Ultimately, Oyallon-Koloski’s video essay gives the viewer a whole new way to look at the work and consider the importance of movement, rhythm, and sound in conveying key themes and nuances in the movie as a whole. The juxtaposition of the two numbers in such a simple (though not simplistic!) way gives viewers deeper insight into the choreographic, rhythmic, thematic, and socio-cultural content and context of an iconic work of theatre and cinema.

Review by Catherine Grant

I very much appreciated and enjoyed Jenny Oyallon-KoIonski’s medium-specific study of a medium-specific aspect of the film version of West Side Story. It's a marvellously horizontal work of mash-up that deconstructs and jazzes up and undoes again the sizzling/cool binary that runs throughout the movie.

The video also brilliantly exploits acousmatic listening, intentionally obscuring the sound identities of the scenes by—quite subtly at times—disconnecting them from their source. And it also performs Michel Chion’s "forced marriage" experiment at the same time, indeed, in the very same deceptive way. I really liked all these defamiliarising games of “now you see me, now you don’t” and “now you hear, me now you don’t”.

The games are a key part of this highly enjoyable parameter-based experiment, and one which Oyallon-KoIonski explains very well. I found that I needed multiple viewings to experience the findings she lists, though. Indeed, I wasn’t able to deduce the editing rules she adopted without reading her explanatory text. But, as the video frames such an engaging experience of the two routines from the film, the multiple viewings and the multimedia aspects of this project as a whole didn’t bother me at all. On the contrary, I felt that the puzzle aspects constituted the genuinely performative research work of invited film analysis. If the viewer takes up the invitation to participate in the highly active viewing process wholeheartedly that performance proves all the richer, I think.

In short, I really liked how this work played with West Side Story's theme (and structure) of “duel rules,” its double-screen play with doubling and fighting performing a kind of analytic code duello. This is a great project that really grows on its viewer, and reveals more with each viewing.