Creator's Statement

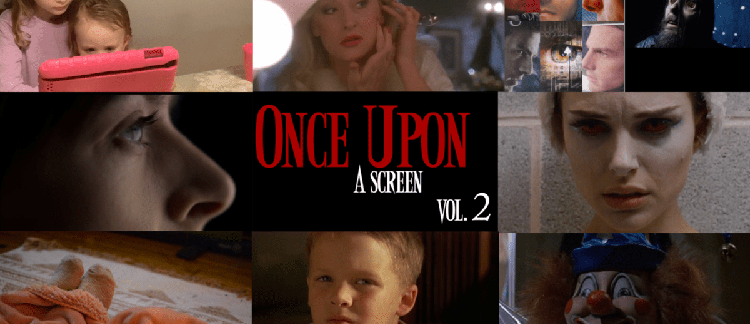

The surface aim of this video essay is to illustrate Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the radical elsewhere (1986: 19) in relation to composition of cinematic images that conceal racy subject matter in R-rated films. My thesis centers on how cinematic acts of offscreen sex insist rather than exist in a figurative space. This references Deleuze’s theory of the radical elsewhere as a place where things are not shown, but felt by the viewer. Adult subject matter is often left to the imagination. The text that I based my video on dealt with the speaker’s sexual awakening at a young age, spurred on by identification with the media object. I sought examples of sex scenes in particular, because it is so common in cinema for sex to be suggested onscreen but not explicitly shown.

At first, I built the structure of the video around a clip from a cheap 1980s American comedy called Pink Motel (Mike MacFarland, 1982). The anonymous text that inspired this video essay mentions the memory of a sexual act that took place off-camera. Pink Motel does feature a sex scene obscured by the framing of a bed that blocks the action. But the sexual act was technically within the boundaries of the frame, and was just hidden by an onscreen object. I soon scrapped Pink Motel from my examples because I decided it was not faithful to Deleuze’s concept. The more I thought about the radical elsewhere, I decided to only include sexual acts that occurred outside the borders of the frame. That seemed truer to Deleuze’s statement that everything outside the frame “insists, rather than exists.”

I chose to visually express the concept of a radical elsewhere as a pink neon outline that I created in After Effects, which signified everything outside of its borders as taking place off-screen. The pink neon and the hum sound effect that accompanies it were inspired by the motel sign from Pink Motel. While I scrapped Motel, I did retain the pink border and it became useful as a visual representation of off-screen space, as well as a mysterious object that compels the viewer’s attention.

It was my initial goal not to assume the sexual orientation of the anonymous source text, and I searched for both hetero and homosexual sex scenes. Eventually, I decided that making some kind of assumption, correct or not, was inevitable in this exercise, and that ultimately, I would be the one considered responsible for whatever assumption or decision I made on behalf of the author. I chose to feature gay sex scenes because I thought they were probably too risqué to be filmed with an explicit approach. Certain shots were composed to exclude incendiary body parts, leaving them to the imagination. This was exactly what Deleuze was talking about.

Originally, I had audio narration throughout the video, but I removed it, which resulted in an enigmatic, experimental approach. This was truer to the nature of my intent; to create a mood and let the textual excerpts carry the argumentative burden. As I edited, the video essay became more and more mysterious, rather than didactic. But while my examples show radical elsewheres in films like Querelle (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1982) and Shelter (Jonah Markowitz, 2007) in concrete ways, my ulterior motive was to establish how this Deleuzian concept is shared across multiple movies. The scenes where River Phoenix sits by a door were meant to suggest that there is a radical elsewhere on the other side, composed of several movies. The technical glitches I embraced further press the dream-like quality of off-screen space, and of the unknown. I feel my video essay can be interpreted in different ways and would not insist that there is only one way to understand it.

Work cited

Deleuze, Gilles. 1986. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

Biography

Philip Józef Brubaker is a writer and filmmaker who makes videographic non-fiction about the art form of cinema and his relation to it. He studied at the Rogue Film School with Werner Herzog and the Experimental Documentary MFA at Duke University. He has made 100 video essays for Fandor.com and is known around the globe for his work.

Reviews

Review by Johannes Binotto

Memory text

I've never talked about this.

I know that I don't have to be ashamed about it but strangely I am.

Are you familiar with that: the memory of affects you once had and how awkward and overwhelming they felt. A memory that is so vivid that it makes you feel embarrassed. Not the same way as then but embarrassed for how you where. For how unprepared and helpless you have been.

I was probably nine years old and alone at home. My parents were just a few houses away, visiting neighbours for dinner. I knew where I could find them. And I started to watch this film that was on TV. I still remember everything about it or rather about this scene at the beginning because I never saw the rest of it. And to this day I never could bring myself to watch the entire film, although I sometimes pretend otherwise, when other people talk about this film or its director.

There wasn't even anything explicit to be seen in that scene. I probably couldn't even show to another person what it was that so upset me. It is impossible to put my finger on it. But then I guess that's exactly what made it so disturbing. That it was happening not in but outside of the frame, in the off space. The characters in the film were doing something to each other I didn't have names or even images for. But of which I knew it was sexual. And it had to do with me.

The off space, says Gilles Deleuze, is not just what lies outside of the frame but a radical elsewhere, of which you cannot even say that it exists, but that it insists. And I guess that's the reason, or one of them, why I am always coming back to this quote. Not because I want to show how well versed in film theory I am but because it is so personal to me. Because it helped me to understand what happened to me that evening. Because it gives words to what I felt then. How insistingly intimate that can be which cannot be shown.

And I also remember how dirty I felt. Not because I had seen something I didn't want to but rather because of the opposite. Because I felt aroused by it, because I felt the film knew me better than I did myself, that the film knew something about my desires, about my lust, about my sexuality I wasn't aware of before. Something so secret that even the film could not show it directly but had to keep it outside its frame.

And I felt so lonely. How to talk about something you can neither show nor name but that you know is there? I turned the TV off, shaking. Do you know that, this feeling when you realize that something has happened that will leave you changed. Like when a knive suddenly slips off and you cut yourself. I was running over to the neighbours house to my parents. I didn't tell them anything. I was pretending to just have been bored alone at home. You must never talk about this, I told myself.

It's not that it is the actual film scene still haunts me today. Now when I think about it I think the scene was probably even meant to be funny and ironic. Perhaps it would make me laugh if I saw it again.

But what haunts me is the feelings I had then. Or, more precisely, this paradox: that I felt the film was showing me something that I immediately recognized as my own while knowing at the same time that it never existed before. Something I had to acknowledge as my very own lust although it was so foreign to me. Something that is right at the centre while remaining in the off space.

And I wonder how this experience is perhaps what eventually forced me to spend so much time with cinema while also making me afraid of it. That I still want to shield myself with knowledge and analytical skill from what made me so helpless in front of the TV. Or that I am secretly wishing to be once again engulfed by that same frightening experience I had 35 years ago.

So I guess, it makes sense that today I am telling you this story but do not even know, who I am talking to. You will never know what it really was that happened to me.

There's nothing to be ashamed of, I tell myself. The secret is kept. Outside.

Author’s Reflection on the video - "Seen from elsewhere"

I was afraid of watching Philip's video based on my text. I felt ashamed, not so much of having overshared in the text that I handed in, but of having forced someone else to deal with my emotional baggage and insecurities. Being so familiar with Philip's videos and admiring his sensibilities made me even more anxious. When I was finally watching it, it was a curious experience of feeling both inspected and camouflaged by the images he chose – thus fitting the dialectics of the inside and outside of the frame I was writing about.

But the real emotional shock came from another elsewhere (sic!) and in a form I never expected. Probably no one would guess that it is this footage that hit me the most: the footage from one of Gilles Deleuze’s lectures where he develops the fascinating and frightening idea of being caught in someone else's dream (an idea that Deleuze saw at work in the films of Vincente Minnelli). Did Philip know how obsessed I have always been with this very passage from Deleuze? Did he know how much it frightens me and how much I am feeling drawn to it at the same time? I feel seen by this video, but seen from a perspective I never thought to be visible.

Biography

Dr. Johannes Binotto is researcher in cultural and media studies, experimental filmmaker and video essayist. He works as senior lecturer for film theory at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts and for American and Cultural Studies at the University of Zurich. Since 2021 he leads the Swiss National Science Project “VideoEssay. Futures of Audiovisual Research and Teaching”. Personal website: transferences.org.